Journal Club: Glial pathology in human temporal lobe epilepsy

Introduction: Glial Cells and the Landscape of Epilepsy Research

This is my first journal club post and today I’m goin to review the paper titled: High-resolution transcriptomics informs glial pathology in human temporal lobe epilepsy by Pai et al. (2022). Which describes glial pathology in human temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) using advanced transcriptomic techniques, namely nuclei sorting purified RNA-Seq and single cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-Seq)1. Their work uncovered cell-type specific dysregulation, particularly in astrocytes and microglia, and provided a transcriptomic framework for understanding seizure pathology at cellular resolution.

This post is also part of my RNA Quest series, a project dedicated to rethinking how we explore, visualize, and communicate high-throughput data. In that project, I used the raw sequencing files and metadata provided by this paper to perform a fresh differential expression analysis of their neuronal data using DESeq2 and custom interactive visualizations. The interactive report can be viewed here.

Background

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is a neurological condition characterized by recurrent seizures originating in the temporal lobes of the brain. Glial cells (astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, microglia) play significant roles in TLE by influencing neuronal excitability, synaptic function, and neuroinflammation. Despite their importance, the molecular signatures of different glial cell types in TLE remain poorly understood. This study aims to investigate glial pathology in human TLE using high-resolution transcriptomics, including bulk and single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq).

Until recently the role of glial cells in neurological disorders was considered relatively unimportant compared to neuronal contributions. Importantly, medical treatments aimed at reducing neuronal excitability has shown limited efficacy. But more recent works, like this paper, have revealed the importance of glial contributions to brain function of disease development. In epilepsy, where neuronal hyperactivity takes center stage, glial contributions are increasingly recognized as both modulators and markers of pathology.

The authors explored the cellular and regional heterogeneity of gene expression in the human epileptic temporal lobe, with a particular focus on astrocytes and microglia.

Study Overview: What Pai et al. Discovered

The paper set out to answer the following question: How do transcriptomic profiles of glial cells differ between epileptic and control brain tissue?

They addressed this with two similar methods each with their own benefits. First, they performed bulk RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on sorting isolated nuclei from fresh frozen human brain tissue from:

- Individuals with medically refractory TLE (surgical resections).

- Post-mortem non-epileptic controls (autopsy samples).

Then they executed single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on whole cell human brain tissue from:

- Individuals with medically refractory TLE (surgical resections).

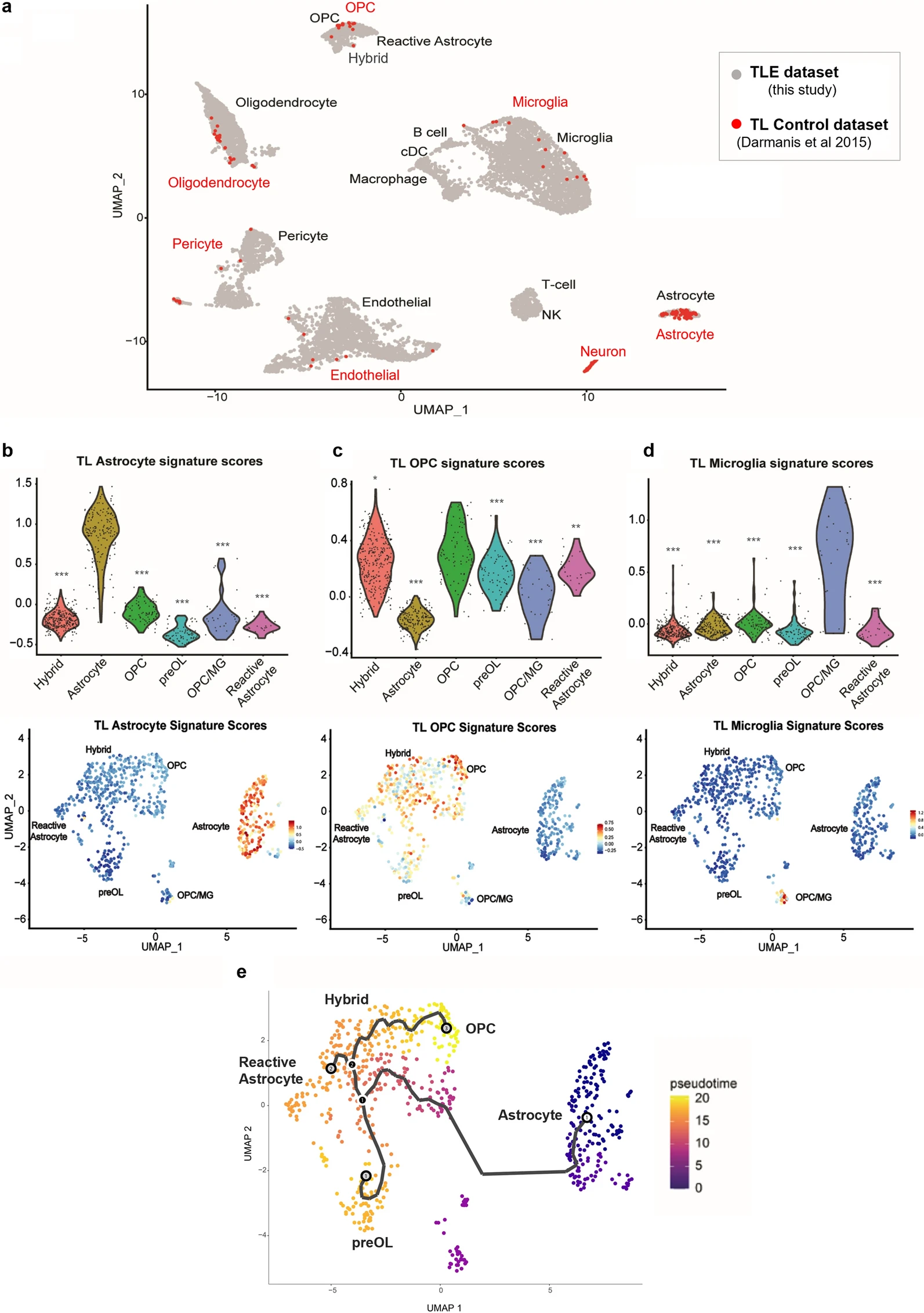

- Previously published Temporal lobectomy samples from medically refractory seizure patients where the locus was deeper than the removed temporal lobe tissue (Darmanis, 2015) (also surgical resections).

Key findings

Bulk Transcriptomics

Bulk RNA sequencing revealed significant transcriptional changes in TLE tissues.

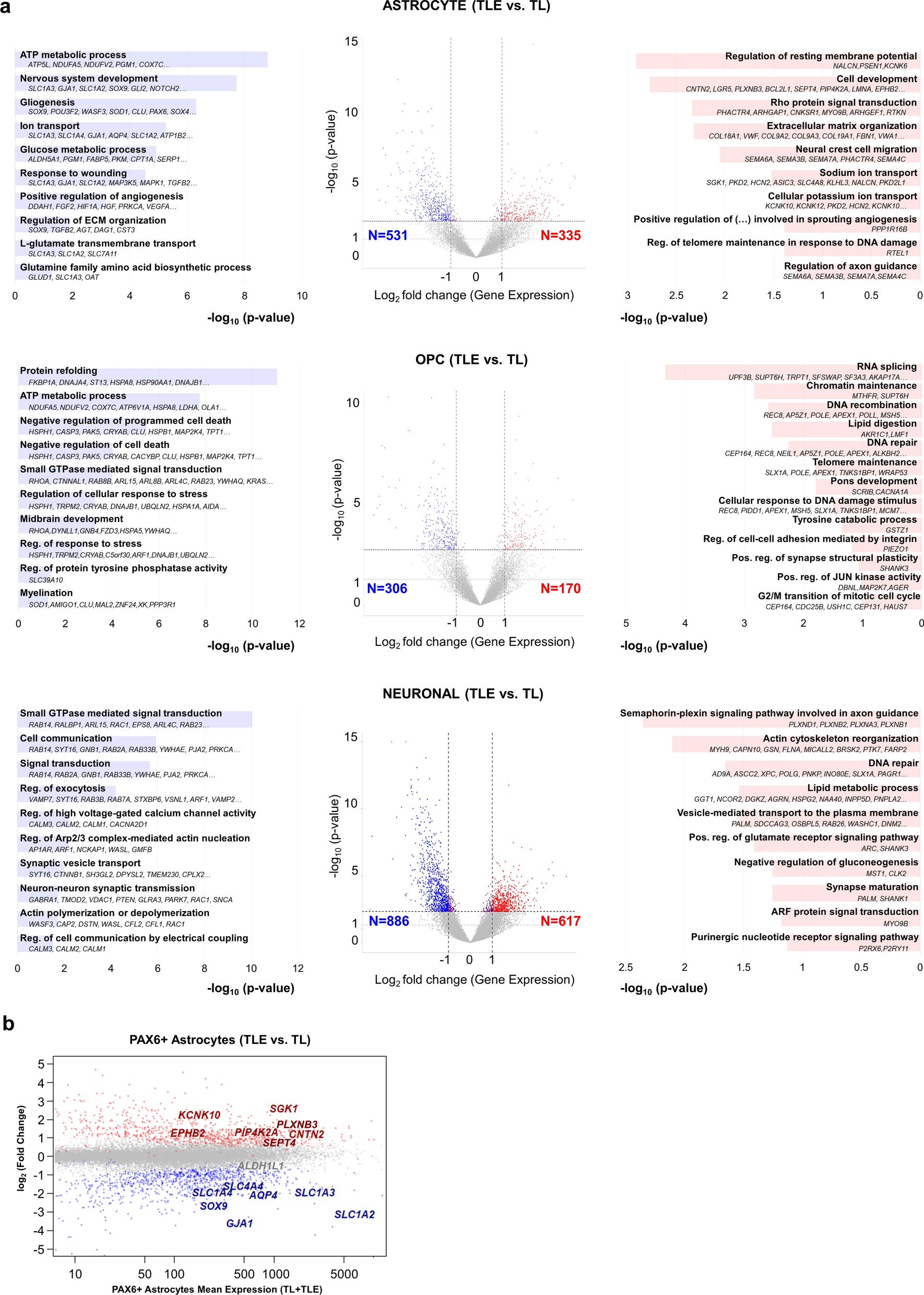

Cell Type-Specific Transcriptomics: The researchers developed a method to isolate nuclei from neurons (NEUN+), astrocytes (PAX6+/NEUN-), and oligodendroglial progenitor cells (OPCs; OLIG2+/NEUN-) from fresh-frozen human neocortical tissue. This approach enabled them to perform nuclear RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) to analyze cell type-specific gene expression profiles in TLE samples.

Astrocyte and OPC Alterations: In TLE samples, astrocytes exhibited downregulation of genes associated with mature astrocyte functions and upregulation of development related genes, indicating a shift towards a less differentiated state. Similarly, OPCs showed distinct transcriptomic changes, suggesting their involvement in TLE pathology.

Neuronal dysregulation: Differentially expressed genes in neurons were significant for gene ontology related to cell communication, signal transduction, and axon guidance, synaptic transport and synapse maturation.

Figure 3. Dysregulated genes and biological processes in human temporal lobe epilepsy astrocyte, OPC and neuronal populations.

Single Cell Transcriptomics

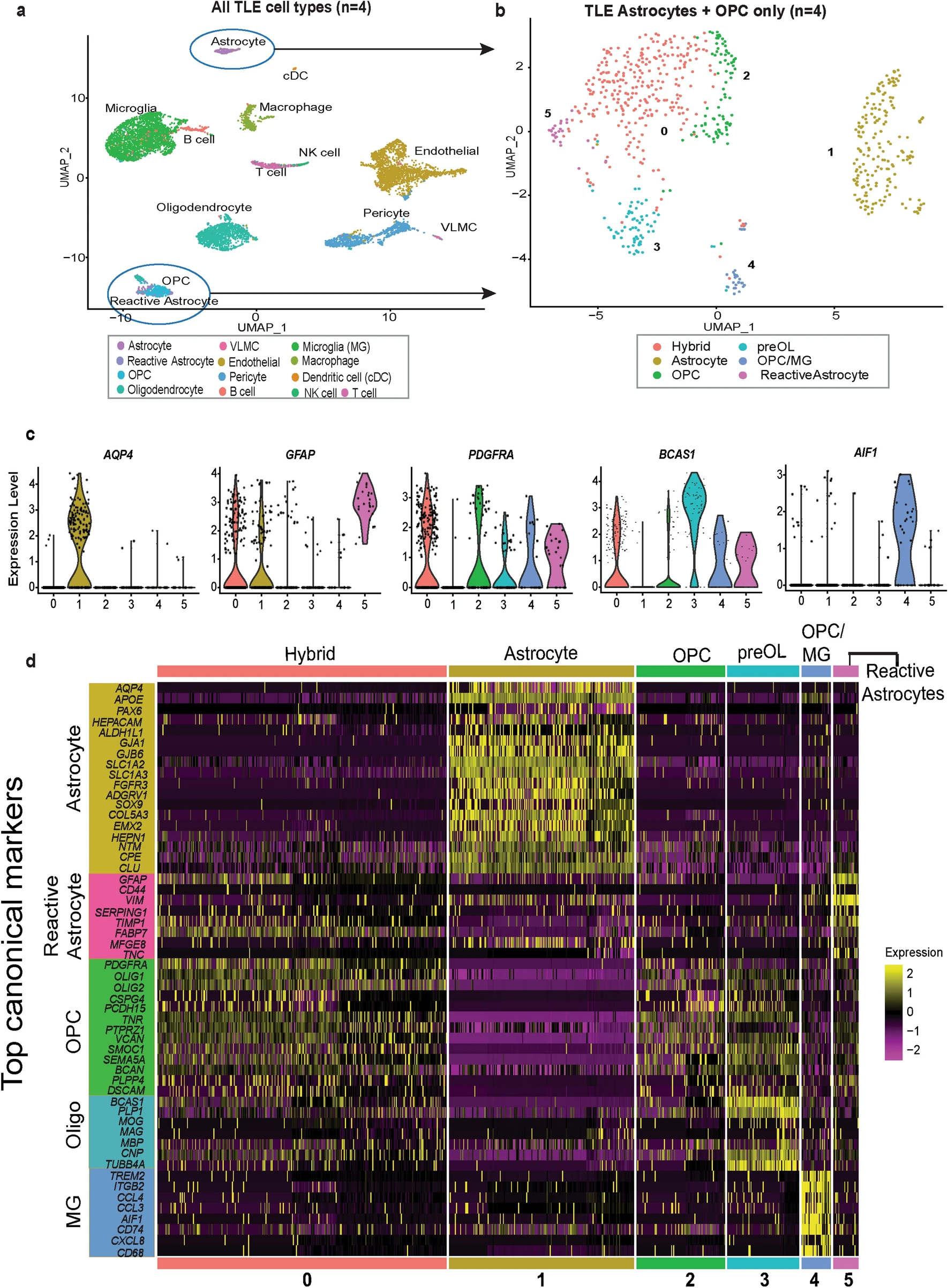

The focus of the paper was on glial cells, also neurons were underrepresented in their scRNA-Seq data so they were excluded from the main body of the paper from this point forward, but they were included as a distinct cluster from the control dataset in figure 5 and in supplementary figure 4 (supplementary file 10).

scRNA-Seq provided detailed profiling of glial cell diversity in TLE compared to controls. TLE astrocytes displayed hybrid states, expressing both reactive astrocyte markers (GFAP) and progenitor-like gene programs. Downregulation of mature astrocytic genes involved in glutamate uptake, potassium buffering, and normal metabolic functions. Abnormal differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) into mature oligodendrocytes. Myelination-related genes were significantly altered. Microglial cells showed activation signatures associated with chronic inflammation and synaptic pruning. Enrichment of immune-related pathways (e.g., NF-kB signaling, antigen presentation).

Figure 4. Single cell transcriptomics of human temporal lobe epilepsy reveals mixed lineage glial subpopulations.

One of the most significant results is that they found a unique hybrid glial population, expressing markers of both reactive astrocytes and OPCs, was identified in TLE tissues. The TLE samples revealed a unique subpopulation of glial cells co-expressing markers of both reactive astrocytes and OPCs, such as GFAP and OLIG2. This hybrid glial population was not observed in control samples, indicating its specific association with TLE. Trajectory analysis suggested these hybrid cells could transition into reactive astrocytes or mature OPCs, contributing to epileptic pathology. Pseudotime analysis suggested that these hybrid glial cells might represent a transitional state, with potential to differentiate into either reactive astrocytes or OPCs. Immunofluorescence studies confirmed the presence of GFAP+/OLIG2+ glial cells in TLE tissue, some of which were proliferative. Functional assays demonstrated abnormal neurosphere formation from these cells in vitro, supporting their altered state.

Figure 5. Comparison of normal and epilepsy temporal lobe scRNA-Seq datasets confirms aberrant glial phenotypes.

Implications:

This study highlights the significant role of glial cells, particularly astrocytes and OPCs, in the pathology of TLE. The identification of a hybrid glial population suggests a complex glial response to epileptic activity, which may contribute to disease progression. These findings underscore the importance of considering glial cell dynamics in the development of therapeutic strategies for epilepsy. Reactive astrocytes impair homeostatic support for neurons, enhancing excitability and promoting seizures. Dysregulated OPC differentiation impacts myelin integrity and axonal function in TLE. Targeting hybrid glial states or inflammatory glial pathways could yield novel therapies for TLE.

Strengths of the Study

The use of fluorescence-activated nuclei sorting (FANS) enabled precise isolation of astrocyte, OPC, and neuronal nuclei from fresh-frozen human tissue. I can speak from personal experience that this method is a challenge. They used human tissue and cells throughout the whole study, so the conclusions of the study are highly relevant to human biology and potential treatment discovery. Findings were corroborated via transcriptional profiling, pseudotime analysis, and functional assays. Most importantly, they validated their omics findings at the bench by observing a proliferative population of cells (Ki67+), that was also expressing OPC and reactive astocyte markers (OLIG2+/GFAP+).

Considerations and Limitations

The biggest potential issue with the study is the controls that were used and the potential batch effects that might stem from them. The bulk RNA-Seq samples were postmortem tissue collected at autopsy whereas the Epilepsy tissue were obtained from surgical resection on living patients. The scRNA-Seq samples were surgical resections for both groups, but the controls here were obtained and processed by a different group altogether. While the authors addressed this concern, it remains a potentially huge source of variability. The study’s sample size for RNA-Seq and scRNA-Seq were also statistically modest. Both of these concerns are common challenges in human brain studies however, so I think they are necessary evils to work with this kind of sample.

Why This Study Caught My Attention

As someone deeply interested in epilepsy, glial biology, and the transcriptome, I found this paper particularly interesting for several reasons. Their emphasis on non-neuronal contributors to epilepsy is part of a broader push in our field to consider cell types outside of neurons, which have historically received the majority of research efforts. Their multi-omics approach allows them to cross-reference their results against each other for greater confidence in their conclusions but also to take advantage of the benefits of each method, for examples greater sequencing depth with bulk RNA-Seq and cell type specific analyses with scRNA-Seq.

Final Thoughts

Pai et al. (2022) delivers a nuanced view of glial pathology in epilepsy, moving the field closer to a systems-level understanding of brain disease. Their work underscores the importance of open data, high-resolution methods, and cell-type-aware analyses in unraveling complex neurological disorders.

For researchers, educators, and students alike, this paper offers both valuable insights and rich material for continued exploration. Seriously, it’s a great dataset check it out yourself!

This study provides high-resolution insights into the transcriptional landscape of glial cells in human TLE. The identification of hybrid glial states offers exciting avenues for understanding the pathophysiology of epilepsy and developing glia-focused treatments.

Further Reading & References

- Original publication: Pai, B., Tome-Garcia, J., Cheng, W.S. et al. (2022) High-resolution transcriptomics informs glial pathology in human temporal lobe epilepsy. acta neuropathol commun 10, 149, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40478-022-01453-1

- S. Darmanis, S.A. Sloan, Y. Zhang, M. Enge, C. Caneda, L.M. Shuer, M.G. Hayden Gephart, B.A. Barres, & S.R. Quake (2015) A survey of human brain transcriptome diversity at the single cell level, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 (23) 7285-7290, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1507125112

- My reanalysis of their neuronal data: RNA Quest

Open data fuels open science.

Stay Connected

If you’re a student, researcher, or just a science enthusiast, I’d love to hear your thoughts. Reach out or follow along via RSS for more deep dives into brain research, data storytelling, and big data reanalysis.

A previous version of this post incorrectly described their methods as “single nuclei RNA-Seq” here and several places throughout this post. The correct method used in both the Pai et al. and Darmanis et al. studies was single cell RNA-Seq. Pai et al. used the Chromium platform from 10x Genomics, while Darmanis et al. used the Fluidigm platform. Those errors have been corrected to reflect the actual methodology used. Thanks to Balu Pai himself for the kind clarification! ↩

Leave a comment